Jack Benny

dr george pollard

![]()

“Jack Benny was arguably the funniest person on network radio,” says Dr Charles Laughlin. “He got laughs doing anything or nothing. A facial gesture, heard on radio, a well-timed pause or a slight shift in vocal tone was enough to put me in stitches.

“Trips down to his Vault were masterpieces. There was a toothless alligator in the moat, an old guard, Ed, and creaking doors. The Vault verged on the surreal, leaving the audience aching from too much laughter,” says Laughlin.

Benny was his best saying nothing. Media silence is a cardinal sin in the USA and surreal. In silence, Benny found the longest, loudest laughs.

“Benny was most adept at the drawn-out, slow, silent take,” says Howard Lapides, the LA-based talent manager. “No one caused such hysteria, with only a look. He’d turn to the audience; his look, always tranquil, part hurt feelings and part perplexity.”

When Benny boasted, too much, Mary Livingstone might say, sternly, “Oh, shut up.” Benny would gaze, silently, at the audience; his hand, perhaps, to his left cheek, his eyes screaming, “Why me.” “The laughter would go on for twenty seconds, which is a long, long time,” says Laura Leibowitz.

The studio audience saw his reaction. Radio listeners imagined it. Either way, Benny caused much laughter and pleasure.

“Knowing when to speak is good,” said Benny. “It’s best to know when to pause.”

Benny is unique for taking, not giving, a punch line that got a huge laugh. “The laugh Benny got was in his reaction,” says Burt Dubrow. “Few stars, then or now, take punch lines, as expertly as did Benny,” says Leibowitz. “Yet, he never became a punching bag.”

“Besides,” says Burt Dubrow, “Jack Benny never stole a line. He didn’t believe he had to get the laugh.” On other shows, script re-writes made sure the star got the laugh. “The laugh came on the Benny show. That was enough,” says Lapides.

Benny built a team of writers, actors and players that created a world. The audience had to learn how to hear the show. “Benny,” says Lapides, “was an inside job: learn to navigate the show, get the jokes and laugh.” “Frasier” was much the same.

The team created, Benny decided. He decided whom to hire, such as writers, actors and players. He approved the storylines or running gags as well as the guests on his shows. These were critical decisions. Benny eagerly bore the weight other stars declined.

Rarely mentioned, Jack Benny created Johnny Carson, who hosted the “Tonight Show” for thirty years before Leno, Conan and Leno. “Carson idolized Benny and Benny loved Carson,” says Burt Dubrow. “Carson adapted much of Benny for his own ends, most notably, the look of bewilderment. This got Carson huge laughs from calculatedly mediocre jokes.”

“Carson wasn’t only a great television comedian,” says Dick Summer. “He was the grand master because of Jack Benny. Both remembered and revered, today, as in their heydays.”

Jack Benny started in vaudeville, says Laura Leibowitz (above), “as did most entertainers of his time.” She’s President and Founder of the International Jack Benny Fan Club (IJBFC). “His first brush with vaudeville came at the Barrison Theatre, in Waukegan, Illinois.” Benny worked as an usher. Later, he played violin in the orchestra, in the pit, accompanying touring acts that played the theatre.

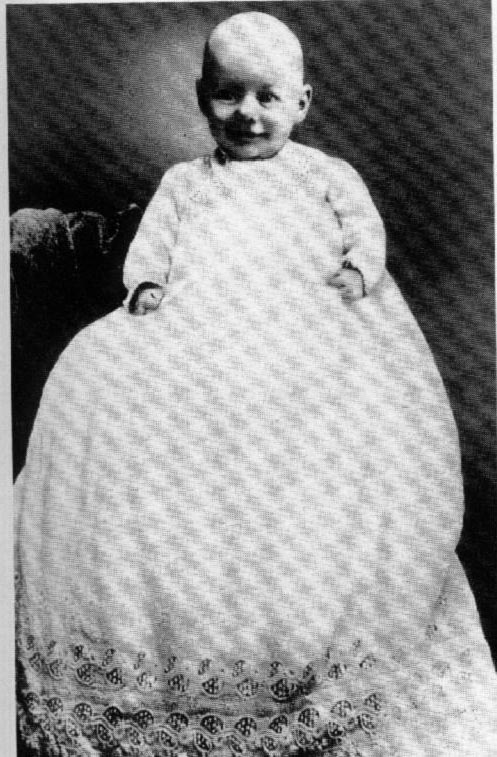

Born Benjamin Kubelsky, on Valentine’s Day, 1984, in Chicago, Illinois, he grew up in Waukegan. His father, Meyer, run out of the tavern trade, owned a haberdashery. His mother, Emma Sachs, encouraged him to play the violin, with hopes of a career in classical music.

At 6 months, 14 and 16 years old '

The Barrison was a small, neighbourhood vaudeville theatre, one block from where Benny lived, in Waukegan, Illinois. “It had maybe 100 seats,” says Leibowitz. Waukegan likely had one or two such theatres. “Variety,” says Leibowitz, “listed no such theatres in the town.”

There wasn’t much nightlife in Waukegan, a small, Midwestern town. The city is thirty-three miles north of Chicago, near the Wisconsin border. About 16,000 lived in Waukegan, in 1911, when Benny began at the Barrison.

Benny left school at age sixteen."The principal called him into his office," says Leibowitz. "He suggested that Jack pursue other things. If he decides to return to studies, he will be welcomed back."

His friend, Julius Sinykin, helped Benny get a job at the Barrison. Sinykin had an interest in show business. He wrote a few short plays performed at the Barrison. The owners liked Sinykin and took his advice about hiring Benny.

The money wasn’t bad, for the day, either. Seems Benny worked about thirty hours a week for $7.50. In 1911, a union worker, in Chicago, earned $21, about 43 cents an hour, for a 48-hour workweek.

Benny was not a typical pit musician. Pit musicians are often jaded. They aren’t the best influence or the best musicians. They play the same music, repeatedly, for the same acts, which soon blur into one.

He enjoyed the acts and developed an addiction to the smell of grease paint. “Jack often laughed, uncontrollably, at the antics of comedians, which was his hallmark,” says Leibowitz. George Burns caused it to happen better than did anyone.

Once, at a party given by singer, Jeannette MacDonald, Burns said to Benny, “Now, you know someone is going to ask Jeannette to sing, probably right after dinner. When she starts singing, I don’t want you to laugh.” As soon as MacDonald began to sing, Benny began to laugh, uncontrollably. He had to leave the party.

In 1911, Benny met the Marx Brothers. They played the Barrison as the “Four Nightingales.” From the pit, Benny laughed uproariously at their antics.

At the time, the Brothers lived in Chicago, giving them ready access to three major vaudeville circuits, the Gus Sun, Pantages and Considine and Sullivan. Their mother, Minnie, managed the act. "She offered Jack a job," says Laura Leibowitz.

Minnie deserves explanation. Born Minna Schoenberg, in 1864, she was sister to Al Shean, of “Gallagher and Sheen,” a top vaudeville act around 1900. She, too, tried vaudeville, but flopped. There was little call for a harpist who yodeled in several foreign languages, said son Groucho.

Around 1905, Minnie developed an act featuring her sons, Chico, Harpo and Groucho. She sometimes used the name Minnie Palmer. The act flopped, but they keep trying. In time, the new act becomes the Marx Brothers.

From the orchestra pit of the Barrison, Benny is “almost bleeding laughter, at the antics of the Marxes,” says Leibowitz. Minnie says, “Great! Why don’t you join our tour? You play the violin for us. We love your laugh. We’ll have a great time.”

Minnie Marx thinks she’s found a built-in audience. Benny asks his parents, Emma and Meyer Kubelsky. They’re Orthodox Jews, already deeply concerned about the crazy boys and wild women their son meets at the Barrison. If he goes on tour, his parents don’t know what will happen to him.

“No,” says Emma, “you will not go on tour with the Marxes.” Benny is 17 years old. His parents are sure touring in vaudeville will lead to his final corruption. They won’t hear of it. Minnie Marx likely wasn’t someone Emma or Meyer Kubelsky found reassuring.

Although he didn’t get to tour, Jack did meet Zeppo Marx. They became friends. Zeppo was the bridge to Sadye Marks.

In 1912, Emma or Meyer Kubelsky let Benny tour vaudeville, with Cora Salisbury. As Benny says, “The Barrison closed suddenly and Salisbury, who’d taken me under her wing, decided to go back to work.” Salisbury needed a partner. Benny needed a job. They developed an act.

Salisbury convinced Emma and Meyer Kubelsky to let him join her on tour. “She knew his parents,” says Leibowitz. 'Salisbury told Emma, “I’ll make sure he gets plenty of rest, eats right and doesn’t run around.” Salisbury was older, 45; maybe she presented as more protective than did Minnie Marx.

The deal was a three-month trial. In September 1912, age 18, Jack took the train, with Salisbury, to Gary, Indiana. They had a three-day booking, a split week.

Left, Cora Salisbury and Benny, about 1912.

Right, sheet music for an earlir hit by Salisbury

As Benny said, “We were killing the audience, with simple, flashy moves. They thought I was doing something impossible. I pantomimed to suggest the terrible struggle I had playing these difficult numbers.”

During this first tour, there was turmoil about his name. “Jack was using his birth name, Ben Kubelsky,” says Leibowitz. A well-known concert violinist, Jan Kubelik, was performing in the same area, as Benny, at the same time. He complained about the likeness of names.

A lawyer, hired by Kubelik, wrote to Benny. He claimed Jack was deliberating misleading the public. Benny changed his name to avoid a lawsuit. “Salisbury and Kubelsky” became “Salisbury and Benny.”

“Years later,” says Leibowitz, “Jack was working as Ben K Benny, in an act called, "Fiddle Funology." Ben Bernie, a well-known bandleader, demanded Jack change his stage name.” Again, Benny complied.

"It appears," says Leibowitz, "Jack was mis-identified, in a listing in weekly "Variety"; it called him Ben Bernie. I don’t know if [bandleader] Bernie actively demanded a change or if Jack was frustrated at the confusion. He changed his name shortly thereafter." Either way, Jack Benny stuck.

The “Benny” is obvious, as his birth name is Benjamin Kubelsky. His friend, Benny Rubin, claims “Jack” was a word sailors used to point out anyone. “Hey, Jack, can you hand me that anchor,” much the way the working class use “Bud” or “Pal,” today.

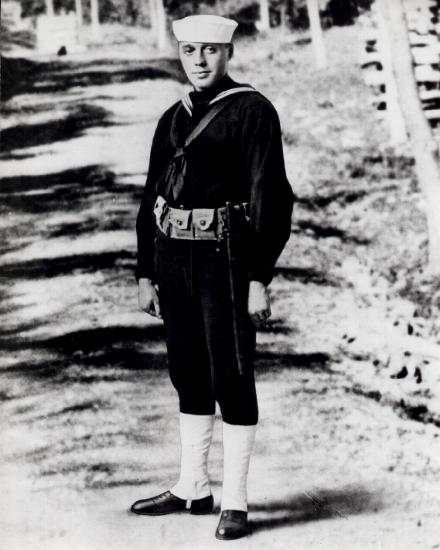

Benny had recently left the Navy. Jack Benny became his stage name. In the late 1940s, he changed his name, legally.

Benny saw many vaudeville acts from the pit of the Barrison Theatre, but “he caught the performing bug earlier in life,” says Laura Leibowitz, of IJBFC. Benny received his first violin, a half size, when he was six, the birth-year of his sister, Florence. He started lessons, right away, moving along quickly; going up the ladder of teachers.

“Many recognized his had talent,” says Leibowitz, “but he didn’t have enough self-discipline.” The violin needs more discipline than do most instruments. Jack couldn’t sit and practice scales, for example, hour after hour; he'd look out the window and get lost in a daydream.

Yet, if relatives or friends visited, Jack arranged a show, in the living room, starring him. He loved performing, but the violin was too demanding. Jack, instead, honed his comedic acting, as a way to get attention.

Jack Benny, the performer, seems born, more than made. “Yes,” says Leibowitz, “but events fall his way. He shows talent, playing the violin. He’s encouraged to put on shows at home. He leaves school, Julius Sinykin advises him. The Barrison Theatre is a block away from his home. Cora Salisbury uses him in her act. Audiences love ‘Salisbury and Benny.’”

After two years touring, Cora Salisbury retired from vaudeville, returning to Waukegan to care for her ailing mother. Jack wants to continue performing. He teams with Lyman Woods

They tour using much the same act as “Salisbury and Benny”; Benny calls himself “Ben K Benny” or “Bennie K Benny. By 1914, “Benny and Woods” are working for $400 a week, split evenly. They had steady work. “That’s vaudeville success,” says Leibowitz, “steady work.”

In 1917, Benny and Woods were booked at the Palace, in New York City. “The Palace was the top vaudeville theatre in the USA, its gold standard,” says Martin Gostanian, the maven of pop culture. “Other theatres booked ‘Palace Acts,’ sight unseen. Playing the Palace was money in the bank, for months afterwards.”

The same awed tones usually go with talk of the Winter Garden Theatre as well as the Palace. “The Winter Garden has its charm and mystic,” says Gostanian, “but the Palace was more impressive. Bert Williams broke the colour barrier, at the top of vaudeville, by headlining the Palace. I don’t think headlining the Winter Garden would have broken the colour barrier or not as easily.”

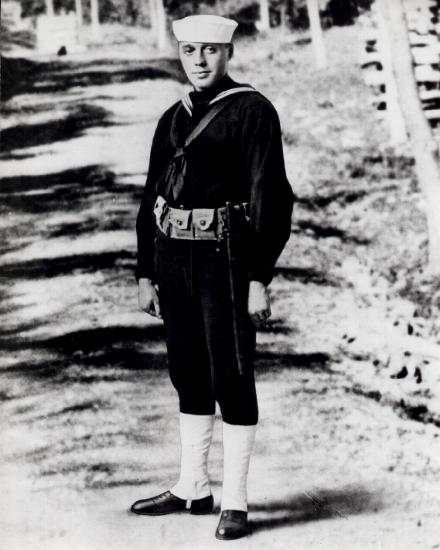

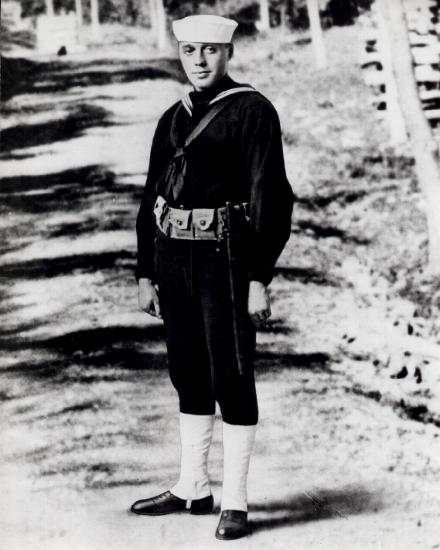

“Benny and Woods got a lukewar review for the Palace show,” says Laura Leibowitz. Benny went back to Waukegan. After his mother died, in 1917, and Woods had moved on, Benny joined the US Navy at Great Lakes (above). He applied for the theatrical company, where he teamed with Elzear “Zez” Confrey. They did a standard vaudeville act, flashy musicianship, rolling eyes and related pantomime.

Dave Wolff, producer of “Great Lakes Review,” for the Navy, asked Jack to audition to speak two lines. “I knew nothing about comedy,” Jack said, “but Wolff liked my reading. I won the role of ‘Izzy There,’ the Admiral’s Disorderly.”

Reading two lines launches a major career. “It’s his first comedy appearance,” says Laura Leibowitz. “Intuitively, he knew what to do. The revue and Jack get good reviews; he’s a natural.”

How does comedy slip into his act? “To this point,” says Leibowitz, “the act was musical. Jack rolled his eyes or made faces at flashy antics. Otherwise, he did all musical acts.”

When Benny performed in naval revues, he discovered comedy. During a revue, he played a violin number, the crowd is numb, there’s no reaction. Someone says to Benny, “Talk to them.”

He says, “I was arguing with Admiral Saltwater, the other day, about whether the Irish Navy or the German Navy is bigger. I said I thought the Jewish Navy was bigger than both of them put together.”

The audience thought it hilarious. Ellis Island, in New York City, jammed with Jewish immigrants, disembarking from ships. The brief story was topical, satirical and widely understood, part of what Sarah Blacher Cohen calls, "Yidn to Yankees," the use of comedy to help assimilate Jews into American society.

Comedy eases into his act, with Zez Confrey. Jack plays ‘Izzy There’ in another naval review. “Now, he wants to do comedy,” says Leibowitz.

Benny expected to work vaudeville, with Confrey, but different naval release dates quashed the idea. When Confrey got out of the Navy, he joined the QRS piano roll company, as a composer. He had a huge hit' with “Kitten on the Keys,” in 1921.

Unable to wait for Confrey, Benny developed a solo act. His act included some music and some comedy. As with most of his career, Benny took his time, moving from music to comedy: no great leaps for him.

“The solo act opened with music,” says Leibowitz. Then Jack talked, a bit, sang, offered a few jokes, some about his fictional “Dumb Dora” girlfriend, and played more music. He ended with the flashy flourish reminiscent of “Salisbury and Benny.”

Slowly, comedy becomes more important. Music fades from his act. Yet, it doesn’t vanish, always available to help him through a bad audience.

In 1922, Jack had his picture on the front page of the sheet music for “Why Should I Cry Over You?” Written by Nathan “Ned” Miller and Chester Conn, “Cry Over You” was a huge hit. It’s probably equivalent to a million downloads, today.

The publisher likely thought Benny would attract more attention than Miller or Conn, who were new to music publishing. It’s also possible Benny didn’t charge a fee for use of his photograph. He likely hoped for larger vaudeville audiences after the sheet music published.

"Ned Miller was the unofficial partner of Jack, for many years,” says Leibowitz. Miller performed supporting roles, for Benny, in vaudeville. Later, Miller played supporting roles on radio and television, too.”

In the early 1920s, Miller worked as a shill for Benny. He took a seat in the audience, an act or two before Benny came out. Miller would heckle, on cue from Benny. He and Benny would go back and forth, with Benny saying, “Got sit by the wall, it’s plastered, too,” and so forth.

Eventually, Benny would become flustered and say, “Oh, if you’re so talented, why don’t come down here and sing a song.” Miller would oblige. He’d sing, beautifully. The audience believed it was true.

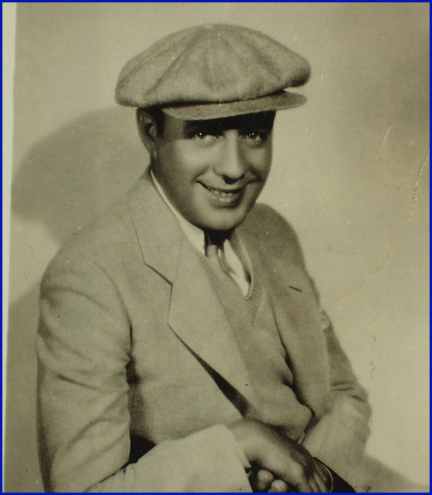

Jack Benny about 1920, 1925 and 1927 '

By the early 1920s, Benny no longer sang or played violin, much. He was the “Aristocrat of Humour,” the best actor using humour. “Still, he takes a violin with him, on stage, needing the security of the prop,” says Leibowitz.

Violin in his left hand, bow in his right hand, Benny talked about generic issues. He told long stories, again, often about fictional girlfriend, “Dumb Dora.” His act closed with a brief flash of “Tiger Rag,” played on the violin.

Benny earned about $450 a week. He often was the next to closing act,' the most coveted spot in a vaudeville show. He was a star.

Now, Benny had money to buy material for his act. He used two writers, Harry Conn and Al Boasberg. His act improved.

Meeting Sayde Marx

At Passover, 1921, Benny and the Marx Brothers were on a bill at the Orpheum, in Vancouver, British Columbia. “Zeppo Marx asked Benny if he wanted to go to a wild party, with many hot women,” says Leibowitz. Benny agreed. The wild party, in fact, was an Orthodox Seder dinner, at the home of a someone Zeppo knew, Henry Marks.

Benny, 27, found 14-year-old Sadye Marks annoying. The feeling was mutual. Next day, Sadye and three of her friends sat in the front row, at the Orpheum Theatre, staring blanking at Jack, during his act.

In 1924, Benny played the Pantages Theatre in San Francisco. As he left the theatre, one night, a young woman tried to get his attention. Thinking she was a “Stage Door Janie,” a groupie, he ignored her.

This was Sadye Marks, all grown up, 17 years old. The Marks family had moved from Vancouver to San Francisco. Two years later, the Marks family lived in Los Angeles, where Jack worked a show with the “Bernovici Brothers.”

Al Bernovici had married Ethel “Babe” Marks, older sister of Sadye. “Jack ran into Babe, backstage,” says Leibowitz, “and accepted an invitation to dinner, with her, Al and her younger sister, Sadye.” Jack claims not to remember Sadye.

During dinner, Benny was smitten with Sadye. “Love at third sight,” he calls it. She claims he ignored her, again.

Sadye worked at the May Company, a large department store, in downtown Los Angeles. The next day, Benny went to the store to talk with Sadye. He siad he bought hosiery, endlessly, so he could talk with her.

Benny continued touring in vaudeville, but stayed in touch with Sadye. At the time, Mary Kelly and Benny were deeply in love; they had a long-standing, if off-again, on-again, romance. She was Roman Catholic. He was Jewish. Marriage was thus unlikely.

After fifteen years or so in vaudeville, Benny wanted new challenges. He wanted a chance to get away from touring. “Vaudeville isolated performers,” says Leibowitz.

“He’d travel to a booking. Someone would put up his card, on stage right. He’d perform. The audience applauded. Someone took down his card.”

Four, five or more times a day, one vaudeville act followed another. Acts rolled across the stage, as overnight trucks on the inter-state, in isolation. There was no continuity.

“Vaudeville was a cafeteria,” says Laura Leibowitz. Each show had a song, a dance and a little seltzer down your pants, to borrow a line from David Lloyd. The goal was to make easy money for the theatre owner.

This frustrated Benny, but revues or follies had continuity. The likes of Florence Ziegfeld, the “Ziegfeld Follies,” produced shows around effortless transitions between acts, a general theme and flow. Ziegfeld didn’t ask the audience to pay top dollar for a string of isolated acts, no matter how great each one.

Around this time, Frank Fay was developing a new character, the wisecracking emcee. Always nattily dressed, the emcee provided comedic transitions between acts. If the audience didn’t care for an act, the emcee could reinvigorate the mood before the next act appeared.

Fay also had a stylistic walk. “Fay didn’t walk onstage,” says Laura Leibowitz, “as much as he glided. His stride was confident and commanding, with an air of smugness.”

Many performers copied the Frank Fay walk. Most notable, among those who copied his walk, were Jack Benny and Bob Hope. Today, few remember or use the Frank Fay stage walk.

“For Jack,” says Leibowitz, “the walk was faux smugness. He cascaded on stage, as the main course to dinner table, saying, ‘Eat me up.’” The sashay walk fit his radio character, nicely.

The idea of transition became important, too. An emcee introduced acts and ensured each show flowed. This took much flare and audiences enjoyed it.

The emcee talked with an act, to promote it or fill time. He could interrupt the act, under, say, the guise of an important announcement. He might conduct an impromptu interview to cover a costume or scenery change.

The emcee role appealed to Benny. He had the flare. He could be part of the complete show, say, two or three hours, weaving in and out, providing the flow and getting much attention. This is the germ of the ensemble idea Benny used on radio; you can hear the emcee in his radio show.

In 1921, Frank Fay had the idea for a revue, “Fables,” that revolved around the emcee. The acts played supporting roles. This experiment didn’t get off the ground, due to financial problems, but Fay gave life to the idea.

Benny wasn’t up for “Fables,” that was for Fred Allen, says Martin Gostanian. In 1926, the Shuberts offered Benny a role in ‘The Great Temptations.’ He took their offer, at $600 a week, although the show featured nudity and some crudeness.

Mostly, Benny emceed “Temptations.” He had a few small roles, as a secondary character in sketches. His main purpose was transition and flow.

Sadye Marks now re-enters his life. “When ‘Temptations’ played Chicago,” says Leibowitz, “Jack ran into Babe Marks-Bernovici. She told him Sadye had become engaged to a wealthy fellow from Vancouver. Jack decided to act.

“Babe called her sister and handed the phone to Jack.'He said, to Sadye, ‘You're too young to marry.’ Then he persuaded her to come to Chicago to talk and rethink her marriage plans. She did.

“Jack took Sadye to Waukegan. She met his father, who approved. When Sadue asked about her being too young to marry, Benny said, ‘Too young to marry him, but not to marry me.’” She ended her engagement.

On Friday 14 January 1927, Jack and Sadye married at the Clayton Hotel, in Waukegan, Illinois. It was an Orthodox Jewish ceremony, conducted by Rabbi Farber. Present were Florence, younger sister of Jack, and his father, Meyer; Babe and Al Bernovici, Julius Sinykin and Sidney Bloch, Assistant State’s Attorney for Illinois. As Jack stomped on the glass, at the end of the ceremony, Sadye fainted.

Benny continued with “The Great Temptations.” Still, he left before the show moved to Broadway. “A famous incident led to Jack leaving 'Temptations',” says Leibowitz.

We may think of the 1920s as grandmother quaint, but “‘Temptations’ featured topless women, jiggling their way across the stage,” says Leibowitz. The content of "Temptations" likely didn’t bother Jack, but later, he let people believe it did.

“When Jack and Sadye married, in 1927, she wasn’t in show business. She spent much time waiting for Jack, as he performed or rehearsed. There were many good-looking women, mostly dancers, around Jack, which Sadye didn’t like.

“During the preview of ‘Temptations,’ in New Haven, Connecticut, a dancer played a prank on Jack," says Leibowitz. "She used lipstick to paint a pig on her left breast. Then she burst into the dressing room that Jack used, flaunting her breast in his face and yelling, ‘Oink, Oink.’”

Benny laughed it off. What’s he to do. Until recently, he was a single man and didn’t have his husbandly reactions down pat, yet.

“Sadye fumed from behind the open door,” says Leibowitz. “Jack didn’t notice her at first. The young woman did and made a hasty exit.

“Jack sees Sadye, eyes raging, daggers coming at him. She goes after him. She scratches his face, deeply, with her fingernails, leaving bloody furrows in his left cheek.'

“A few minutes later, Jack goes onstage. He’s holding his left hand to his cheek, to cover the scratches made by Sadye," says Leibowitz. That becomes his trademark posture.

“I give credence to the showgirl story," says Leibowitz. "It's backstage. Everyone is doing high-jinx to ease nerves or pass the time. Still, the young woman did it in front of Sadye.”

When Benny left “Temptations,” he knew he couldn’t leave Sadye home, while he toured in vaudeville. He developed a new act that included Sadye, using the name Marie Marsh. By the end of their first year touring, she was a hit.

Sadye sang well. She played the “Dumb Dora” character, popular at the time, well. She had superb delivery.

On the last leg of their vaudeville tour, movie producer Irving Thalberg saw them. He wanted Benny at Metro-Goldwyn Mayer (MGM). Benny took up the new medium and its challenge, right away, as well as the $750 a week salary for six months.

His first role was in "Chasing Rainbows," which, most sources agree, floped. “Hollywood Revue” was next, in 1929. “Revue” a series of appearances by actors signed to MGM. Benny played himself in a weak skit, with Conrad Nagel; weak.

Two movies and four shorts, in two years, wasn’t enough for Benny. He asked Thalberg to release him from his contract, even after receiving a contract extension and pay raise. He and Sadye moved back to New York City.

Benny on Broadway

In 1930, Benny had an offer to play Broadway. “Earl Carroll signed Jack for his ‘Vanities,’” says Laura Leibowitz. “Jack emceed, did a long monologue and acted in several sketches, including portraying Abraham Lincoln.”

In one sketch, Benny enters a farmhouse, carrying a young woman in his arms. “I just resuscitated your daughter,” he says to the farmer.

The farmer replies, “By golly, then, you’ve got to marry her.”

Blue for the time, maybe, it wasn’t the “The Great Temptations.”

In another sketch, Benny portrayed a private detective. The script called for him to smoke a cigar. At 36-years-old, Jack had never smoked.

During rehearsals, the cigar made him ill. He pleaded to stop using the cigar. The director prevailed.

Eventually, “Jack came to like cigars,” says Irving Fein. “For the rest of his life, he smoked the occasional cigar. Yet, Jack never developed a taste for expensive cigars; he always smoked the cheap ones.”

Benny earned $1500 a week for “Earl Carroll’s Vanities.” A typical worker, in 1930, earned $15 a week and the unemployment rate was 25 percent. Jack Benny was a star.

The Network Radio Ago

Benny left “Vanities” early in 1932. “The show was going on tour,” says Leibowitz. “Sadye didn’t have a part in ‘Vanities,’ but she had a small career of her own, such as working with Benny Rubin on a radio show pilot. Jack didn’t want to leave her home.” He left "Vanities," saying he wanted to stay in New York City to try radio.

No one knows, for sure, what Benny did to break into radio. There are rumours he recorded a pilot show. He likely made the rounds: networked. in a literal and figurative sense.

“On Tuesday 29 March 1932," says Leibowitz, "Jack made his first radio appearance on the ‘Ed Sullivan Show.’ It's interesting that Sadye debuted on radio before Jack. In 1929, Benny Rubin used her as his partner in a pilot that an advertising agency bought.”

Ed Sullivan, a former boxer, was entertainment writer for the New York “Evening Graphic.” He also hosted a show on WABC-AM, now WCBS-AM. The show featured new talent, which is another way of saying low pay or unpaid audition.

Benny wanted to make a great first impression. He hired Al Boasberg, one of his vaudeville writes, to help work on the monologue for the “Sullivan Show.” Benny opens with, “This is Jack Benny. There will now be a slight pause while everyone says, ‘Who cares?’”

Radio was corny in 1932. “Yes,” says Leibowitz, “but Douglas Coulter, of N. W. Ayer advertising agency heard Jack and liked him. The next day, the story goes, Coulter convinced Canada Dry to use Jack for its new show promoting Ginger Ale. A few weeks later, Monday 2 May 1932, the ‘Canada Dry Program’ airs on the NBC Blue Network.”

The Canada Dry show featured Benny, bandleader George Olsen and his wife, Ethel Shutta. Ed Thorgenson was the first announcer. Sadye Marks joined for the 3 August 1932 show.

Listening to the first show for Canada Dry, Jack seems more emcee than headliner. The music leads. Jack has a few minutes between musical numbers, songs and commercials.

The show moved to CBS on 30 October 1932. Ted Weems and a string of other bandleaders replaced George Olsen, Ethel Shutta left and Sadye Marks became Mary Livingstone. The 15-minute show ran Sunday at 10 pm and Thursday at 8:15 pm, both original episodes.

Newspaper radio editors voted Benny the “Most Popular Comedian on the Air,” for 1932. He won against strong competition: Eddie Cantor, Ed Wynn, Fred Allen, Burns and Allen, Jack Pearl, as Baron Munchausen, and the Marx Brothers. Yet, after the CBS run, Canada Dry dropped Jack.

“[It] didn’t like Jack kidding the product,” says Leibowitz. On one show, Benny told a story. “While walking through the desert, I came across a caravan of explorers who had been lost in the Sahara for six weeks. Their water supply was gone. They were dying of thirst. Quickly, I rushed to them and gave each one a bottle of Canada Dry Ginger Ale. Not one of them said it was bad drink.”

“Listeners loved the kidding,” says Leibowitz. After a seven-week break, Jack returned to NBC, with a new sponsor, Chevrolet. His 30-minute show aired Friday at 10 pm until the summer break. It returned 1 October 1933 at 10 pm on Sunday.

For Chevrolet, Frank Black was the bandleader. Benny added a tenor to the cast: first, James Melton, then Frank Parker. Howard Clooney was the announcer until the end of the year, when Alois Havrilla took over. Mary Livingstone was on the show, too.

On 6 April 1934, the show changed name and sponsor, again. For “The General Tire Show,” Benny added announcer Don Wilson and bandleader Don Bestor. Mary and Frank Parker stayed.

Starting in fall 1934, General Foods used Benny to promote Jell-O. The first “Jell-O Program” aired at 7 pm, east coast time, on Sunday 14 October 1934,” says Leibowitz. Mary and Don continued. A new tenor, Kenny Baker, joined in 1935.

Phil Harris joined the cast, in 1936, as the supposed bandleader. It’s his character and no more, although he may have worked with the orchestra from 1936 to 1938. Still, “Harris had his own orchestra, unrelated to the show, and several hit records," says Leibowitz.

“Mahlon Merrick was the de facto music director from 1938 or so until the 1950s. When the radio show toured, Harris pretends he’s leading the band. On the show, Merrick does the heavy lifting.”

A valet, “Rochester,” portrayed by Eddie Anderson, debuted in 1937. “Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin, the writers, intended ‘Rochester’ as a one-time character,” says Leibowitz. As many of their ideas, "Rochester" became a pillar of the show.

Anderson did a dance act in vaudeville. On the Benny show, he was an instant audience favourite. He joined the show, permanently, six weeks after his first appearance.

In search of a new tenor, in 1939, Jack ventured to New York City. During the audition for Owen Patrick Eugene McNulty, they took a break. When Jack reconvened the audition, McNulty was talking with his accompanist.

Jack yelled, “Owen; oh, Owen McNulty.” From across the hall McNulty says, “Yes, please.” This broke up Jack. He couldn’t stop laughing. McNulty got the job and a name change, to Dennis Day.

Mary Livingstone, Don Wilson, Phil Harris, Eddie Anderson, Dennis Day

Benny, the vain, tone-deaf and untalented violin player, becomes a running gag, about 1935. “When you see Jack playing, says Leibowitz, “on television, he is playing the violin. Radio was different. To play, Jack had to put down the script, pick up the violin and settle it, under his chin, before he could play. After he played the violin, he reversed these steps.

“The set up and take down took time. It was hard to write-around the setup, which disrupted the flow of the show. On radio, Jack playing the violin was rarely feasible.

“Larry Kurkdjie usually played the violin for Jack. He was in the orchestra on the show. For a while, Kurkdjie gave Jack formal lessons, off air.

Jell-O was not a major product until General Foods attached it to Benny. Invented in 1897, Jell-O moved through several owners, until landing at General Foods. It languished far behind Knox Gelatin for want of attention.

Users added a flavour to Knox. Jell-O came prepared, in six flavours. This was an exploitable advantage.

“In 1934,” says Leibowitz, “General Foods decided to sponsor Jack. He became the spokesperson for Jell-O, much the way Bill Cosby was forty years later. Don Bestor wrote the J-E-L-L-O jingle that rose over a five-note scale. When Jack appeared, he’d say, ‘Jell-O Everybody.’”

“Jack and Jell-O fit as a glove,” says Leibowitz. He increased sales of Jell-O, significantly, and kept sales high. Still, the Second World War soured the relation between General Foods and Benny.

Jell-O is gelatin. Gelatin comes from boiled bones, connective tissue and animal intestines. The basic ingredients of Jell-O were among the first items rationed during the war.

“General Foods couldn’t meet the demand for Jell-O,” says Leibowitz. It cut back on advertising Jell-O to bring demand in line with supply. There was no rationing of breakfast cereals. Sales of Grape Nut Flakes, a breakfast cereal, could increase endlessly. As of 1942, Jack was the spokesperson for Grape Nut Flakes.”

In 1944, Lucky Strike cigarettes involved a total change of style for Jack. “Oh yes,” says Laura Leibowitz. "George Washington Hill ran the American Tobacco Company from 1925 to 1946. He was a pill. Lucky Strike used hard-sell commercials.”

Hill built Lucky Strike on a strategy of making it acceptable for women to smoke, in public. His only tactic was hard sell. Yet, he took to the comparatively mild-mannered Benny, fast and well.

The General Foods advertisements were calm and genuine. Try Jell-O, you’ll love it. Lucky Strike rammed cigarettes into the lips of listeners.

Leibowitz attributes the best description of the Lucky Strike commercials to Martin Gostanian, the maven of pop culture. “He says, ‘You hit the dog on the nose with the newspaper. You hit dog on the tail with the newspaper. You pet the dog on the middle.’”

That’s the format of the Lucky Strike spots. Basil Ruysdale, an auctioneer, opened the Benny show, in hard sell. “Sold, American,” he said. Lucky Strike buys the best tobacco. Kenny Delmar says, “Right.”

There’s a similar spot at the end of the show. “ There you have two whacks with a newspaper,” says Leibowitz. “In the middle of the show, the ‘Sportsmen Quartet’ sings a comedy commercial; a novel arrangement of a popular song reworked into a Lucky Strike commercial. That’s petting the muzzle.”

Benny parted with General Foods in 1944. “Jack left General Foods,” says Leibowitz, of the IJBFC, "not the other way round. During the early 1940s, his audience shrunk. There were many more shows, more choice. Wartime controls hurt radio shows, in unseen ways.” Benny couldn’t mention the weather, for example, other than in a most generic way: it rained, the other day.

These and other stresses worried Benny; what were the prospects for his show. Doubt made him a bit edgy. Slowly, he introduced changes in the show. “To change sponsor, too, made sense,” says Leibowitz.

Maybe the hard-sell success of Lucky Strike boosted his confidence. The company sponsored another highly popular show, “Your Hit Parade.” Lucky Strike was the top-selling cigarette, in 1944, too. Nor were its executives beneath stroking the Benny ego.

Benny also had a run in, of sorts, with an executive from General Foods. “On a train trip,” says Leibowitz, “Jack and [the] executive talked. The executive said to Jack, ‘You should watch it.’ Jack thought it a reference to the slight slippage in his ratings.”

Maybe, Benny thought, General Foods was losing confidence in the show and him. He was making much money for General Foods. It took him off Jell-O because it couldn’t keep up with the demand, due to wartime rationing.

Benny was creating much of the demand for Jell-O. If General Foods worries about his ability to sell its product, maybe he should look for a more confident sponsor. He did.

Lucky Strike doesn’t fit Benny. Did he take what he could get? “Possibly,” says Leibowitz. “Still, although he slipped to fifth spot, in the ratings, his audience was huge. Many sponsors courted Jack. Lucky Strike won.”

Benny went with the sponsor he thought wanted him most. George Washington Hill talked with Benny, personally, about the deal. So, too, did many company executives.

Lucky Strike expressed strong belief in Benny. Its advertising agency, Ruthrauff and Ryan, changed the “Sold, American” auction theme, of the commercials, for Benny. It was hard to resist the Lucky Strike bid.

Why did the hard sell strategy work on the softer-toned Benny show? “Timing is one answer. His audience peaked in the 1941 season, with a share pg 36.2. About 43 million women, children and men listened to Jack each Sunday at 7 pm.”

Forty-three million is about twice a most-viewed “American Idol” episode, today. It’s half the audience of a typical “Superbowl.” An average episode of “Two and a Half Men,” with Charlie Sheen, had an audience of fifteen million.

“By 1944, Jack slipped to 26 share and the show ranked fifth,” says Leibowitz. “The audience hovers at that level for three years. The show slowly grows routine, safer. I think Jack senses a need for change. The taste in comedy was changing, which explains the rise of Bob Hope. Jack needed a way to get his large audience back.”

In practice, Lucky Strike didn't change the show that much. “If you remove the opening and ending commercials, ‘The Lucky Strike Program’ doesn’t seem much different from the Jell-O version,” says Leibowitz. Benny worked between the hard sell commercials. After “Speedy” Riggs, F. E. Boone and Kenny Delmar hard sell the opening, jovial Don Wilson introduces the show. The comedy commercial was enjoyable and interesting. Many listeners tuned out or went to the washroom as the end-of-show commercial began.

“The smaller audience, in 1944, and changes in the show are coincidental, not causal,” says Leibowitz. Previously, the cast worked as a group, a strong ensemble. In 1938, it was typical to involve two or three characters, at one time. Benny, Andy Devine, Don Wilson and Mary Livingstone engage in conversation, leading to a punch line about how Benny can’t find a girlfriend.

In the early 1940s, it seems fewer characters engage at one time. Benny talks with Don Wilson, to open the show. Then Mary comes along and Don fades. Phil Harris might join Mary and Benny, but they fade when Dennis Day shows up to sing.

In later years, Benny talks to the characters one at a time, often Don, Mary, Phil and Dennis; a guest arrives, after Dennis sings, a skit is performed. “The characters are in a revolving door,” says Leibowitz. “It strikes me as mechanical.”

This is the first half of the show. “Yes and the format hastens when Dennis and Phil get their own shows, in 1946,” says Leibowitz. “The Phil Harris and Alice Faye Show” follows Jack. Phil must leave Jack by 7:15 pm, to warm up the audience for his show.” The recording and touring career, of Dennis Day, takes off after the war; he’s busy and sometimes absent.

By the late 1940s, the show could air in sitcom mode, completely. During the first half, Benny works through the characters. A song by Dennis bridges to the second show. The second show is often a movie satire, maybe, involving a guest promoting his or her movie, record and so forth.

Mary and Don most always work the sitcom. Add Benny and the guest, there are four characters. Listeners hardly miss Phil and Dennis.

"You wouldn't be so smart if my writers were here,"

said Jack Benny to Fred Allen

during a seering exchange of ad-libs.

The Benny radio shows moved through eras, linked to writers. “Yes,” says Leibowitz. “Eras seem important for Jack. The Harry Conn era ran from 1932 to March 1936; Mary and Don joined during this time. Convinced he was the sole reason for the success of the show, Conn made outrageous demands. When Jack didn't meet the demands of Conn, he, Conn, abandoned the show, without a script.

“Bill Morrow and Ed Beloin replaced Conn. During their time, April 1936 until June 1943, Phil Harris, Eddie ‘Rochester’ Anderson and Dennis Day joined the show. Al Boasberg, Howard Snyder and Hugh Wedlock contributed during these years, too. These writers formed a solid base for Jack.

“The war years had a different feel, maybe due to censorship and such. In 1943, four new writers took over, Sam Perrin, Milt Josefsberg, George Balzer and John Tackaberry.” Perrin and Blazer stayed with Jack for the rest of his life.

“Morrow and Beloin get the blue ribbon from me,” says Laura Leibowitz, President of the International Jack Benny Fan Club. “They are the most involved writers; both play small roles on the show. Al Boasberg is helping, too, punching up the lines.

“In the 1930s, radio was new and open to ideas. The show didn’t have the mantle to carry that it did from the middle 1940s onward. The stage fright, which overtook Mary later, wasn’t obvious, in the 1930s.

“‘Rochester’ is a new character in 1937. In 1939, Dennis Day is a fresh character. Both help Morrow and Beloin reinvigorate the show.”

By the 1940s, the stakes increased. The sponsor changes twice. The audience ratings wobble during the war. Stage fright overtakes Mary; she opts out of many shows, at the last moment. There are wartime limits. Dennis joins the Navy; he’s gone for two years.

After the war, television comes into play. Phil Harris and Dennis get their own radio shows, but stay with Benny, which causes some issues. The 1940s were tighter, less spontaneous than the late 1930s. There were different challenges and higher stakes.

On radio, Benny relied on writers 'more than, say, did Fred Allen. Benny used writers in vaudeville, but didn’t rely on them. In vaudeville, Benny told Bob Thomas, of the Associated Press, “You didn’t have to worry about writing [all the time]. If you got a good act together, you could play it for seven years. You were in a different town every week.” When you returned to a town, the audience had forgotten your act.

On radio twice a week, in 1932, Benny filled about 12 minutes of time. In effect, he needed a new vaudeville act each week. Thus, Harry Conn helped with the writing.

Benny offered strong comedy for Canada Dry. It was a good balance with the music. Benny never faced the huge writing challenge, alone. He built an ensemble that included writers, cast and “things,” such as his car, the Maxwell, voiced by Mel Blanc, and his Vault.

“Jack was successful, in radio, mostly because he used writers, well,” says Leibowitz. Interestingly, Fred Allen pushed Jack to use writers, although he didn’t make much use of them, himself. George Burns, of “Burns and Allen,” pushed Benny in this direction, too.

As Burns told Bob Thomas, in 1974, he and Benny told stories more than jokes. One line led to another. The story was funny, not only the lines. This called-for writers.

For Benny, the show, especially in the 1930s, told a story. The characters, Jack, Mary, Phil, Don and Dennis, traversed a storyline. Exchanges among the characters made the show interesting and funny.

To flush out the characters, find storylines and make the show more than a string of jokes, took focus and imagination. This wasn’t a task for one person. Developing continuity and flow took an ensemble of writers and actors.

Benny kept his writers much longer than did almost any other performer. The Bob Hope style, rat-a-tat topical jokes on different subjects, pushed him through writers as a hot knife through butter. Milt Josefsberg, for example, stayed with Benny for ten years, Sam Perrin for twenty-five.

The stability and loyalty Benny gave his writers, his ensemble, was a huge part of his success. It bolstered his confidence and theirs. If the writers were uncertain about their relations with Benny, the “I Can't Stand Jack Benny” contest would not have happened.

Mel Blanc, Benny Rubin and Benny with Sheldon Leonard as "The Tout"

The Benny radio shows had many defining moments. “On the 7 January 1945 show,” says Leibowitz, “three notable ideas appear for the first time. I call this the Nirvana show.

“Mel Blanc, train dispatcher, says ‘Anaheim, Azusa and'Cucamonga.’ The line gets a huge reaction; it becomes a running gag.The break between ‘Cuc’ and ‘Monga’ comes later.

"The Vault appears, too; previously, Jack had a safe. From 7 January 1945, the Vault has a combination lock and a guard, portrayed by Joe Kerns."

"His trips down to his Vault were masterpieces,” says Dr. Charles Laughlin, doyen of network radio and Neuro-Anthropologist of considerable note. "There was a toothless alligator in the moat, an ancient guard and creaking doors. The Vault verged on the surreal, leaving his audience arching from too much laughter.”

"Finally," says Leibowitz, "this show introduced ‘The Racetrack Tout,’ who gave Jack unsolicited advice about odds.” He’d say, “Hey, Bud, Bud, come here,” at the racetrack, in a grocery store or near a bank of elevators. “White potatoes are three-to-one over the sweet kind, today” or “Elevator two is six-to-four over elevator three to make five floors without a stop.” Benny Rubin originated the role of "The Tout"; Sheldon Leonard may be most remembered, as he played the role on radio and television.

"'Why I can't stand Jack Benny,'

that's what we'll do," said Benny.

"Not in twenty-five words, but in fifty words."

In 1946, a daring idea pushes Benny back on top to stay. '“The ‘I Can’t Stand Jack Benny’ contest is a huge part of renewing the show,” says Laura Leibowitz, “and the character. Using his left hand to cover the scratches Mary inflicted is a most defining moment in the career of Jack Benny. The contest showed how confident he was in his radio character and is thus defining.”

George Balzer told Leibowitz the story, of the contest. “When we got off-air on Sunday night,” he said, “we never knew what we were going to do for the next [show]. Somehow, by Tuesday, we had an idea. Well, Tuesday, 20 November 1945, came and we hadn’t thought of anything.

“Wednesday morning we, Perrin, Josefsberg, Tackaberry and I, went to see Jack, at his home. We said, ‘Nothing is happening.’ Maybe, if we all sit here together, for a while, something will come up.’

By noon, Wednesday, we still had no show. [Perrin] said to [Jack], ‘Why don’t we have a contest where we ask listeners to write lyrics for a song.'Merrick can put a melody to them. Then, we’ll have a contest.’

“Jack says, ‘No, I don’t want to go through that.’'We’re thinking a little bit more and I said, ‘Jack, here's an idea.'You know, we hear so much on the radio, [such as] I like so-n-so toothpaste in twenty-five words or less to win a prize. You like so-n-so potato chips in twenty-five words or less.

“Why don’t we ask people to write in and say, “I can’t stand Jack Benny because,” in twenty-five words or less. We give the best one a prize.’ There’s total silence in the room.'

“The other three writers look at me. Benny looks at me. I don’t know what to do.

“[Benny] gets up from his chair and walks across the room. He puts his hand on my shoulder and says, ‘That’s it. That’s what we’re going to do.’

“We said, ‘Jack, you can’t.’ He said, ‘It’s what we’re going to do and not in twenty-five words or less. We’re going to give 50 words or less.’

“We did it.'We were looking for one show.'We ran the idea for eleven weeks.

“‘I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” played on Benny as victim. We stroked each of his character traits over three months: vanity, violin playing, his boasting and so forth. The ratings spiked.”

The decision to go ahead took much nerve. “Yes,” says Laura Leibowitz. “The judges for the contest were comedian and writer, Goodman Ace, actor Peter Lorre and Fred Allen.” On joining the judging panel, Allen said, “I’m the greatest living authority on Jack Benny. I’ve seen him reach for his pocketbook.”

The contest received 277,000 entries, about one for every thousand listeners, which was unprecedented. It took four weeks to decide on a winner. The ratings skyrocketed.

Carroll P. Craig, of Pacific Palisades, California, won the contest. Second prize went to Charles S. Doherty, of Cleveland, Ohio. Joyce O’Hara, of Detroit, Michigan, won third prize.

Ronald Colman and his wife, Benita, were regular guests on the show. Coleman read the winning entry, on 3 February 1946. “I can’t stand Jack Benny because ‘he fills the air with boasts and brags, and obsolete, obnoxious gags. The way he plays the violin is music’s most obnoxious sin. His cowardice alone, indeed, matched by his obnoxious greed. And all the things that he portrays show up in my own obnoxious ways.”

Craig captured the character Benny played. As Colman said, after reading the winning entry, “The things we find fault with in others are the same things we tolerate in ourselves.” We find the character, Jack Benny, one way or another, in ourselves.

The contest fit the character Benny portrayed, well. “Jack built the show focusing on his faults,” says Leibowitz. Another story fits here.

“One show, in September 1949, involved a Hollywood bus tour. Jack only appears in the last five minutes.

“The tour guide says, ‘Now, on your right, we’re now passing the home of Jack Benny.’ Jack says, ‘This is where I get off, driver.’

“A phone call, from William Paley, who ran and mostly owned CBS, at the time, came immediately after the show. Paley says, ‘Jack, you have [guts] for appearing so little on your show. It was a debut show, too.’

“Jack says, ‘It was a good show. It got many laughs. Tomorrow, people will say wasn’t the Jack Benny show funny last night.’”

No matter who gave the punch line on his show, Benny got credit for the laugh. The ensemble worked to his benefit. Most comedians find it difficult to allow others to evoke the laughter. Benny, a comedic actor, found it easy.

“There are many stories about other radio comedians that reveal the opposite,” says Leibowitz. “During a rehearsal for, say, Eddie Cantor, a line, spoken by a secondary player, might get a huge laugh. When the show airs, Cantor says the line and gets the laugh. There are similar factual stories about most comedians, but not Jack.”

Frank Nelson always got a huge laugh for saying a stretched, “Yes?” in response to Benny. As Benny told Paley, the audience is laughing at something heard on my show. Around the water cooler, at work, the next day, their saying, “Did you hear Frank Nelson on ‘The Jack Benny Show,’ last night?”

A live show, at the Palladium, in London, England, revealed how confident the Jack Benny character had grown. “Frank Nelson told me the story,” says Laura Leibowitz, of the IJBFC. “Jack is playing the Palladium for the first time. Supposedly, after a brief introduction, he sauntered out, using his characteristic gate. He stood, in the middle of the stage, looking at the audience. He didn’t say a word.

“Someone laughed. Others began to laugh. Finally, everyone in the theatre was laughing, uproariously.

“Nelson said the laughter continued for two minutes, growing more intense by the second. Jack would look into the wings and give a shrug, saying, in a look, ‘I don’t know why they’re laughing.’ Eventually, someone from the second balcony yelled, in a Cockney accent, ‘For gawd’s sakes, Mr Benny, say something.’”

Jack denied, up and down, the yell came from a plant, a shill, in the audience. Using a shill wasn’t beyond Jack. He worked this angle, with Ned Miller, in the 1920s.

"We won't use him,"

was a typical Benny comment about a potential on his,

who didn't like the script or rehearse enough.

Irving Fein suggests Benny didn’t use many guests, on radio, at least until the war years, because of his search for excellence. Typically, guests rehearsed the show once or twice. Benny didn’t think he could get a strong enough performance, with such little preparation.

“It took time for Jack to get rolling on guests,” says Leibowitz. “The ‘Mills Brothers,’ were guests in the 1930s, as was Frances Langford. Otherwise, in the earlier days, guests were far between.”

A story about Grouch Marx makes point about Benny and guests. "The idea fell flat," says Leibowitz, "and may reflect what Fein claims." Early in the week, Groucho read a draft of the proposed script. He panned every idea, every word, and not in a nice way; he wanted to use his own material.

"The writers talked with Jack about the changes Groucho wanted. The comedy of Jack Benny, says Stephane Kanter, 'was as circumscribed as a minuet.' Grouch would use the Benny writers or not appear.

Grouch refused. "We won't use him," said Jack, referring to Groucho. "Jack wasn’t going to get what he needed from Groucho," says Leibowitz. Why waste time, when you can do something else as effective.

A few years later, Groucho guested with Benny. Groucho approved the script, with no trouble. It wasn’t a great show, the script keeps too tight control on the eccentric Groucho.

During an exchange, Groucho alluded to his earlier exclusion. He said to Benny, “Why am I never on your show?”

Benny said, “Because you’re difficult.”

Then, referring to the handwritten ideas, offered by the writers, years before, Groucho said, “I read anything they print for me.”

A search for perfection likely led Benny to have fewer guests other shows.

“By the 1950s,” says Leibowitz, “guests became expensive for radio. Once Jack is on television, regularly, the number of guest stars on radio drops. One budget paid for radio and television. As well, by 1951, Jack and the show were in transition, trying to move viewers and sponsor, smoothly, from radio to television.”

Benny was a perfectionist, when it came to the show. “He fine-tuned each show,” says Leibowitz, “as if a high-performance sports car. If anyone, Jack, a cast member or a guest, messed up, he fumed.”

He didn’t fume often, but he fumed. “Gisele Mackenzie (above) was a frequent guest on the show,” says Leibowitz. “Once, after a show, Jack blows into her dressing room and says, ‘When you delivered [such-and-such] line, you were off by a tenth of a second!’

“She looks at him and says, ‘A tenth of a second! My gawd; you know, how important is that!’ He cowers a bit and says, ‘Well, it was wrong.’”

Benny noticed everything about the show and spoke out when a performance wasn’t as perfect as he wanted. Maybe a tenth of a second is stretching. Still, the MacKenzie anecdote makes the point.

Frank Nelson and with Benny, on television

Yet, Benny allowed the ad-libbed “Drear Pooson” line. “ Frank Nelson told Laura Leibowitz the “Drear Pooson” story. “Early in a show, announcer Don Wilson blew a mention of the newspaper columnist, Drew Pearson. He called him Drear Pooson.

“Nelson said, ‘No one had come up with a line for me on this show. After Wilson blew the Drew Pearson name, the writers called me into the production booth. They said, ‘When Jack asks you if you’re the door attendant, say, ‘Well, who do you think I am, ‘Drear Pooson.’’

“‘No,” said Nelson, ‘you don’t ad-lib with Jack Benny.’ The writers said they’d take the fall for the ad-lib. I read it.

“‘When I delivered the line,’ said Nelson, ‘Jack began to laugh. His eyes got like big saucers. He grabbed the microphone pole, slide all the way down and pounded on the floor. Jack staggered all over the set, in hysterics.’”

In a tightly timed live show, ad-libbing is costly. Fred Allen knew the trickiness of timing. Many network comedy shows ran over. time "Sorry folks, we’re out of time," was not an unusual sign-off. More than once, mistimed laughter led the network to cut the Benny show before the skit finished.

The timing of a show includes laughter and applause. If they guess a line will get five seconds of laughter, but gets 15 seconds, the show runs over. Fifteen seconds expands, as the show moves along. One delay leads to another.

On radio, Benny worked silence to evoke laughter. When a robber said, “Your Money or your life,” Benny took several seconds to answer, as the laughter built. The robber, portrayed by Eddie Marr, had to provoke a response, saying, “Look bud, I said your money or your life.”

Jack Benny and Fred Allen feuding, 1937

The Jack Benny and Fred Allen feud is an endless fascination. It’s a pop culture relic. Yet, the facts of the feud are often mistaken.

“In December 1936,” says Laura Leibowitz, “Fred Allen began the feud, which lasted twelve weeks. An unscripted part of the Allen show, “Town Hall Tonight,” featured a 10-year old violinist, Stuart Canin. He played ‘The Bee,’ by Shubert, masterfully. After the performance, Allen said, ‘A little fellow, in the fifth grade at school and already he plays better than does Jack Benny.’

“Allen made this comment on the east coast version of his show. In 1936, a network show was performed twice, once for the east coast and, later, for the west coast. The networks wanted to maintain a sense of immediacy and spontaneity for listeres on the west coast. The cast and crew would do a show, live, for the east coast, say, at nine pm. They’d return at midnight to do it again for the west coast.

“Therefore no one knows exactly what Allen said on the west coast version that Jack heard. No recording exists." Later, Jack claimed Allen said, "[Jack Benny] should hide his head in shame. The horsehairs in his bowstring want to crawl back under the tail of the horse. The cat-gut, of his violin strings, wants back into the cat."

“At the end of that show, Jack says, ‘Mary, take a letter to Fred Allen. Tell him I’m not ashamed of my playing. I could play ‘The Bee.’’’

Jack aired at Sunday 7 pm on the east coast. Allen aired Wednesday at 8:30 pm. There was ample time for each to work up a good response. Each week, Allen egged on Benny.

In 1954, Allen said, about the feud, “I didn’t plan anything. I didn’t want to explain how [it] was good for [my show]. With our smaller audience, it would take an academy award display of intestinal fortitude to ask Jack to participate. I’d be hitching my gagging to a star. All I could do was hope Jack would have some fun with the idea and that it could be developed.”

“Allen and Benny went back and forth,” says Leibowitz. “In March 1937, Jack took his show to New York City, where the Allen show originated. Jack and Fred Allen stage a boxing match, at the Pierre Hotel, to settle the feud.

“The match never took place. Jack and Fred go out into the hall to settle matters, immediately. They return, arm in arm, singing the song, ‘Friends.’”

Allen saying he hitched his gagging to a star sums up the reasons for the feud, best. Benny finished that season in second place; Eddie Cantor had a strong number one show. Allen was far behind.

Allen had nowhere to go but up and the feud served no special purpose for Benny. “True,” says Leibowitz, “but Jack sowed the germ of a feud. His 5 April 1936 show featured a sitcom called, ‘Clown Hall Tonight.’ Jack supposedly wore a clothespin on his nose to mimic Allen; he starts laughing, uncontrollably, as the sitcom begins.

“By the way, ‘Clown Hall’ was the first show scripted by Ed Beloin and Bill Morrow. They hit their first show out of the park. It was a great start for them.”

On a lost show, from 1936, there’s an extended sketch about the feuding Hatfields and McCoys. The allusions are clearly to Benny and Allen. The idea existed before the Canin incident, if only in half-baked form.

Allen quietly hoped Benny would go along. “He figured Jack would catch on,” says Leibowitz. “At the least, it gave Morrow and Beloin material to focus their writing. The publicity didn’t hurt either show, even if Allen benefited more.”

The feud fits the “Charlie Brown” character Benny portrayed. “The late Eddie Carroll,” says Leibowitz, “likened Jack to ‘Charlie Brown.’ We laugh at adult foibles in the actions of children. Jack was an adult Charlie. ‘Bluffing and blustering his way through life,’ said Carroll, ‘somehow making it.’

“Mary saying to Jack, “Shut up,” is akin to ‘Lucy’ pulling the football away, just as ‘Charlie’ sets to kick it. ‘Linus’ and Dennis Day are alike, too. On radio, the character, Jack Benny, succeeds, not on strengths, but despite flaws, as does Charlie.’”

Each listener succeeded much the same way. “We see ourselves in Jack or ‘Charlie,’” says Leibowitz. “There is the appeal. I think the characters are general and slip across cultural lines, easily, and across time, too.”

During the feud, Fred Allen played “Lucy” to the hilt. He holds the football. Benny, as “Charlie,” takes a long run to give the ball a good boot. Allen pulls the ball away as Benny kicks at it.

Allen says Canin plays better than does Benny. Benny says he can play “The Bee.” Allen says Benny should put the strings of his violin back in the cat and the horsehair in his bow back on the horse. Benny says the bags under the eyes of Fred Allen make him appear as a butcher looking over two pounds of raw liver. Allen says Benny isn’t cheap; he has short arms and keeps his money low in his pockets.

“They went on this way for three months,” says Laura Leibowitz. “Neither gets the upper hand. Two evenly matched sides: the writers for Jack against the wit of Fred Allen.

“It was great radio. The audience loved it. Allen got a ratings boost.”

Eventually, Allen wins. “In May 1946, Jack guests with Allen. The show ends with Jack stripped to his boxers, yelling, ‘I’ll get you for this. You haven’t seen the end of me.’ To which Allen says, ‘It won't be long, now.’”

Back to CBS

As of 4 January 1949, Benny moved back to CBS from NBC. This is a defining, telling moment in entertainment history. To help promote the move, CBS temporarily changes it name, from the Columbia Broadcasting Company to Check Benny Sundays.

Irving Fein says, in 1944, Benny re-signed with Lucky Strike for two years. The deal paid him $22,000 a show. From this money, Benny paid the cast, writers, a musical arranger and bandleader, 17 musicians and for sound effects or other materials necessary to produce a complete show.

Lucky Strike provided and paid-for broadcasting facilities. NBC and Lucky Strike had a separate deal for airing the show. Benny earned about $2000 a show.

That’s much money. The average wage was less than $30 a week, at the time. Minimum wage was 43 cents an hour.

“Yes, it is good money,” says Leibowitz, “but not as much as other radio stars were making. Jack had the number five show. Lucky Strike considered him the best sales person on radio.

“Arthur Lyons, his agent, hadn’t negotiated a big enough deal. Jack needed more money. He took matters into his own hands.”

Earlier, the Music Corporation of America (MCA) turned “Amos and Andy” into a corporation, which increased their earnings, substantially. That impressed Benny. He took action.

Benny talked with Taft Schreiber, the top agent at MCA and company Vice-president. Schreiber says MCA wants to work with Benny, but not if he has another agent. Benny pays off Lyons and signs with MCA.

“Immediately,” says Leibowitz, “MCA forms a corporation, Amusement Enterprises, Inc., to produce radio shows or movies and such. The company, not an individual, puts together the show, negotiates with Lucky Strike and NBC. Jack gets a separate deal, with Lucky Strike, for his services.

“Schreiber asked Lucky Strike to re-open the contract. A clause in the 1944 deal gave Lucky Strike an automatic 3-year extension, if it wished. Schreiber asked Lucky Strike not to act on the extension.

“Surprisingly, Lucky Strike wants to re-do the deal, with Jack. He’s called their greatest asset. The company wants to lock him in for more than three years.”

Lucky Strike offers to pay Benny separately from the cost of the show. He gets $10,000 a show for his services, through 1953. A separate corporation forms to produce the weekly show; it gets $27,500 for each radio show.

“This was a hefty increase all around,” says Leibowitz. “Lucky Strike didn’t mind. Its need was for the ‘comedy commercial’ to be a fixed part of the show. Lucky Strike paid about one million dollars, in 1945, to produce 35-to-39 new radio shows a season.

“There was likely some profit from producing the weekly show and the company produced other entertainment, such as movies. In another context, some suggested Jack earned $12,000 a week. MCA made a great deal for Jack. NBC and Lucky Strike didn’t care as long as Jack showed Sunday at 7 pm.”

David Sarnoff, of NBC; Benny and William S. Paley, of CBS

A few years later, in late 1948, anyone who baulked at the 1946 deal was a genius. “Yes,” says Leibowitz, “Jack sells Amusements to CBS, where the show moves. If he doesn’t have the separate agreement with Lucky Strike, for his personal services, selling Amusements, the show and the move were not possible.

“Prior to forming Amusements, Jack was little more than an employee of Lucky Strike and NBC. His marginal tax rate was 77%. The company, Amusements, paid him dividends and capital gains taxed at about one-third the wage rate.

“Jack got $2.26 million from CBS for Amusements,” says Leibowitz. Robert Metz suggests CBS was willing to pay $3.2 million. NBC offered $2.26 million, but wanted a few days to mull over the deal and didn’t ask Benny to hold off on other bids, while it pondered.

“Paley, at CBS, got wind of the delay,” says Laura Leibowitz. “He and his legal team flew to Los Angeles. They give the NBC offer a quick read and accept it as written, on 11 November 1948.

“Lucky Strike stayed out of the negotiations, expressing no network preference. Its position was clear. Lucky Strike went where Jack went.

“The first CBS show aired 4 January 1949, a week after the last show on NBC. The average rating for the show, on NBC before Jack left, was 24. Paley promised Lucky Strike a $3000 refund for every rating point Jack lost on CBS. Jack was a huge hit; the show went up 3 points in the ratings.”

The refund offer to Lucky Strike was a gambit. Paley put Benny on each of the 400 stations in the CBS network. Alaska heard him live, for the first time, on CBS.

NBC aired Benny on about 225 stations. Almost doubling the number of stations carrying Benny cut the risk for Paley and CBS. It was a clever move.

More than dollars and cents led Jack to sell and move. “NBC showed little interest in buying Amusements. Why buy what it already had?” David Sarnoff, who ran NBC, saw talent as, “A lot of sweet air,” says Metz.

Paley, at CBS, respected and enjoyed talent. “Jack didn’t know Sarnoff; they met and that was about it,” says Leibowitz. One evening, Paley spontaneously called Benny to discuss the move.

“The lawyers, accountants and agents discussed the deal,” Paley said to Jack, “but we haven’t.” They talked. Paley flew to Los Angeles and met with Benny, at his home. This turned the tide, in favour of CBS. Paley profited from respecting talent.

CBS invested, heavily, in Benny. Paley believed listeners tuned to talent, not stations; at NBC, Sarnoff took the opposite position, favouring technology over on-air talent. Benny said he’d urge his friends to move to CBS and did.

Poor human relations cost NBC. “Yes,” says Leibowitz. “The Paley style likely made the deal. Jack had a sweet spot at NBC. There were many reasons for him to stay at NBC.”

The Internal Revenue Services (IRS) challenged the CBS deal with Benny. When Benny claimed the CBS deal as a capital gain, the IRS charged Amusement Enterprises was a personal property holding company, not eligible for capital gains. Benny fought the IRS to the Supreme Court and won.

The floodgates opened after this ruling. “Most NBC talent left for CBS,” says Leibowitz. “Among the top radio stars at NBC, only Fred Allen along with Phil Harris and Alice Faye stayed. Milton Berle stayed, but his radio career was minor; he was the first major star of television, though, on the NBC Television Network.”

Paley made a personal plea that motivated Benny, not unlike what Lucky Strike did in 1944. It was more the Paley style than simple strategy. Still, there was there another reason for him leaving NBC.

“John T. Cahill may have been the final insult,” says Leibowitz. “Sarnoff hired Cahill to act for NBC in its negotiations with Jack. He, Cahill, had history with Jack.

“In 1939, Jack and George Burns bought jewelry, while in France, from a charming fellow who turned out to be a con man. The seller insisted there was no need for Jack or Burns to pay the customs duty. He had a diplomatic pouch to bring the diamonds into the USA.

“Customs officers caught the con man. He involved Jack and George Burns. Jack and Burns pleaded guilty, hoping to avoid publicity. The judge levied a fine and suspended sentence.

“Jack had to appear in court, in New York City. The judge treated him as a deplorable criminal; Jack felt humiliated. The judge wondered, aloud, how a man that earned [so much money a] week could fall for such an unscrupulous scheme. When Jack slouched, in shame, on the back of a chair during reading of the facts into the record, the judge snapped at him to stand up straight.”

It was terrible for a revered person to engage in a tawdry crime. Making it worse was that Benny was generous, endlessly helping new talent and charities. The district attorney that prosecuted the case was John T. Cahill.

Paley was personable. Benny liked that. Sarnoff, distracted by technology, misplayed important circumstances.

Benny and Television

Benny did his first television show after moving to CBS. “It was a pilot, filmed in 1949,” says Leibowitz, “an experimental show filmed in the CBS radio studios. Time swallowed the show, but we know the guests were Isaac Stern, ‘Lum and Abner,’ the Andrews Sister and Eddie Anderson as ‘Rochester.’

“The pilot confirmed Jack could take his style and content to television. On 28 October 1950, he did a live show from New York City. CBS recorded it for airing on the west coast. His opening line was, ‘I’d give a million dollars to know how I look.’”

The first television show ran 45 minutes. Benny believed an hour was too long. After that, his shows were half an hour; except for specials, which he did after his weekly show ended.

Benny eased into television. “In 1949 and 1950, Jack did one television show each year, but he did three shows in 1951,” says Laura Leibowitz. “Part of his pace was budget. Radio and television shared the same budget: each television show cut deeply into the radio budget.

“As well, after the move to CBS, Jack pre-recorded more of the radio shows. Now, he could repeat shows, not only scripts. This opened more time for touring and television, not to mention earnings.

“Jack had much to lose, as he moved to television. His radio show was now permanently number one. It could likely have gone on another five years, without losing money.”

Television is far more demanding than is radio. The technology is complex. Watch the credits at the end of any television show to see how large the crew.

A minor change in television leads to many other changes, some major and time consuming. Relighting may be necessary or new camera angles and makeup. It may take hours for small changes to take effect.

Radio was fast. Don Wilson misspoke the name, Drew Pearson. Moments later, the writers penciled in a back-reference for Frank Nelson to say, Drear Pooson. Such a response is mostly impossible on television.

Television time is expensive. Jack couldn’t stand and look at the audience for more than few seconds. A 30-second laugh cost the same as a 30-second commercial.

Fred Allen complained about television technology breaking the flow of a show. “No doubt,” says Leibowitz, “but as Allen also complained, television ate ideas and scripts ten times faster than did radio. Television is a demanding medium. It calls-for more learning and rehearsing.

“Jack wisely took baby-steps into television because he didn’t want to undermine his number one radio show. Milton Berle and Sid Caesar jumped right in to television; neither had much of a radio presence to protect. They could bet the farm on television and did.”

Both Berle and Caesar were phenomenally successful. In a few years, both were gone from weekly network television, never to return. Benny had a regular network television show for 15 years: “Jack took time to learn about television and fit his style to it,” says Leibowitz.

The radio show ended on 22 May 1955, with no fanfare. “It was the last radio show of the season,” says Bobb Lynes, co-host of “Don’t Touch that Dial,” on KPFK-FM, in Los Angeles, California. “I’m not sure anyone realized it was last weekly radio show, ever.”

Benny with Eddie "Rochester" Anderson; "in-one" with Johnny Carson

There was a huge difference between radio and television for Benny. “On radio, Jack relies on the ensemble,” says Leibowitz. “It’s the 'Lucky Strike Program, starring' a core of five actors and a player or two, such as Frank Nelson and Bea Bernadet. On television, Jack is the centre, with actors playing roles around him.

“Yes, Don Wilson is on every television show and 'Rochester' is on frequently. Dennis appears, sometimes, Mary rarely and Phil Harris never. Jack carries the television show, usually with a guest. He’s able to succeed without the ensemble.”

Most Benny television shows open “in one.” That is, Benny works alone, in front of the curtain, delivering a brief monologue; the last vestiges of vaudeville. Many of his television shows end this way.

A sitcom show might involve Benny, “Rochester” and a guest star. Walt Disney guested, on a later colour special, to promote “Mary Poppins.” Jack wants tickets for his friends. When Disney discovers Jack is trying to sell the tickets, he sends his pet tiger after Benny, who opens an umbrella and sails away, Mary Poppins style. On another shows, Jack dreams he and Marilyn Monroe take a sea cruise.

For another version of the television show, Benny does a monologue. The guest, say, bandleader Bob Crosby, comes out. They talk, maybe sing, dance or perform a brief sketch. Though there might be a player or two in these shows, the focus is on the guest star and Benny.

“Television scripts often came directly from radio scripts,” says Leibowitz. “Someone steals his car, the Maxwell. Jack goes to the Beverly Hills Police Department, to report the theft, and discovers the police dogs are standard Poodles, not German Shepherds. This storyline appeared twice on television.

“Jimmy Stewart and Gloria Stewart replace Ronald Colman and Benita Colman on television, using the radio scripts. Another borrowed script involved Jack going shopping and his radio nemesis, Frank Nelson, is the grocer. The television show ends with Nelson pushing Jack out of the store, in a grocery cart.

“There was a legacy of material, from radio. Scripts used on television were often fifteen years old. Adding visuals made old story lines new.

Benny with Humphrey Bogart, 1955; Marilyn Monroe, 1953

“It’s worth noting how open Jack was to working with his guest stars,” says Leibowitz. Bogart and Monroe made their first television appearances with Benny. “Jack made television less scary for many top stars from movies, theatre and radio,” says Leibowitz.

“Jack also worked well with newcomers, as if they were old hands. He let Shari Lewis steal a show. Jack worked with Lambchop and her other puppets, superbly. Lewis dances and sings, showing the breadth of her talent.

“On one show, Dennis Day had a singing competition, of a sort, with a new group, “The Lettermen.” Jack worked with Frankie Avalon, who was trying to record a new hit: Jack’s envious and keeps interrupting the session until he gets to play on the record.

In 1962, a Filipino group, “The Rocky Fellers,” performed “Long Tall Sally,” with Jack singing back up, wearing an Elvis wig and swiveling his hips. “About the time colour television begins,” says Leibowitz, “Jack has a special featuring the ‘Beach Boys’ singing ‘Barbara Ann.’ Another special featured ‘Gary Pucket and the Union Gap’ singing its hit, ‘Young Girl.””

It was humour through generational opposition. “Yes,” says Leibowitz. Funnier, perhaps, and more daring was having the "Smothers Brothers" on the show, in 1965. Non-conformists, they outwit every attempt by Jack to fit them into a straitjacket comedy formula. For their effort, the “Smothers Brothers” guest on the final weekly “Jack Benny Show,” in 1965.

His flexibility showed most with the Marquis Chimps (above). “Yes, two shows featuring the Marquis Chimps got his highest ratings on television,” says Leibowitz. Benny sits on a small, chimp-size chair. When he starts playing the violin, the chimps leave the stage, in obvious disgust.

“The television show wasn’t only about old hands, such as George Burns or Bob Hope," says Leibowitz. Jack willingly passed the torch. Many others did not.”

“I’m too young to know Benny on radio,” says Burt Dubrow, creator of the “Jerry Springer Show” and “Sally,” “but I know him on television. He was unlike any other comedian, probably ever. Benny never gave himself the joke.

On radio, Frank Nelson gave a 25-second laugh line, Drear Pooson. Bob Hope got a 17-second laugh calling Dennis Day “an E-flat idiot.” The laugh was 32 seconds long, when Andy Devine closed the show, calling it the “new Jelly series.”

“On television,” says Dubrow, “Benny would take the punch line and look at the camera. In effect, Benny was saying, ‘Why me? How’d I get in the middle of this mess?’ Why am I the punch line? 'His reaction got him laughs, probably bigger laughs than anyone else on the show.”

On radio, listeners imagined the Benny reaction as the punch line hit. Viewers saw it in his remarkably hilarious eyes. Although the effect varied, by medium, the result was the same: uproarious laughter.