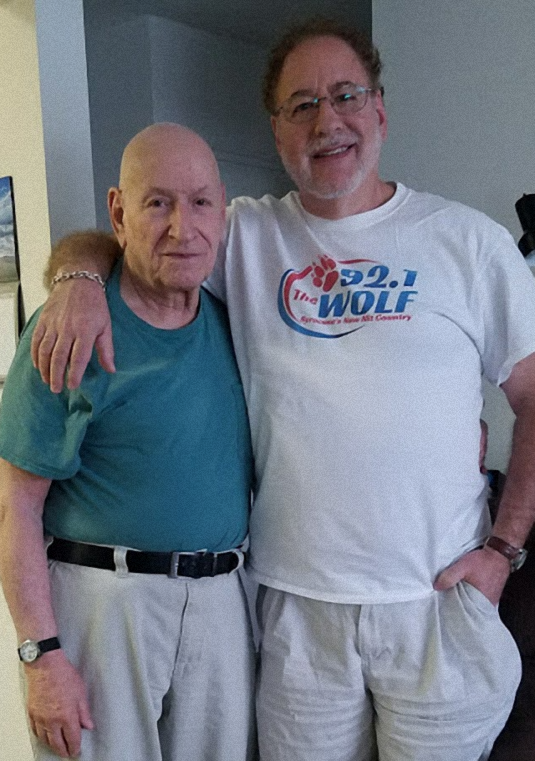

Father and Son

Matt Seinberg

Shelly Seinberg with son Matthew.

In June of 2019, my 90-year-old father, Shelly (above), came to live with us after my oldest daughter Michelle moved out. It took me almost a year to convince him to leave his apartment of thirty years, in Syracuse, New York, to move to Long Island. Several of his friends told him the move was the best for him and that he should do it; finally, he relented and decided it was the best for him to live with us.

Re-locating dad to our home.

I made a one-way plane reservation to Syracuse and booked the same hotel I used previously. His apartment was way to small and unless I wanted to sleep on air mattress, it wasn't going to work. The hotel offered a nice breakfast and Take with Lunches.

Once back at our home, dad settled in well. I got him set up with all the physicians he needed. He also enjoyed spending time with my father-in-law, Mort. The had lunch together at least once a week.

Since it the summer, we'd go outside after dinner and talk about life. He told me of his auto accident, when he was in the Air Force; it led to his honorable discharge. His right arm was so damaged that he spent months at a hospital in California before going home to Brooklyn.

His mother was a teacher. She kept him on a very short leash, whereas his father was an easy-going optometrist. Dad became an optician in 1954 and stayed in that field until he retired, on disability, in 1986.

Dad said if he had his way, he would have stayed in California and started a whole new life. As he was an only child, he felt obliged to be near his parents. He joked that had he stayed in California, that conversation would have been much different; my life certainly would have been.

As the weeks went on, Dad slowed down. He was becoming more forgetful, sleeping more, eating less and falling more, as well. I was taking him to the physician more and more often

In January, the circumstances came to a head when I suggested he give up his car. It wasn't safe for him to drive anymore, with his slower reflexes and forgetfulness. Even though he had On Star directions in his Chevy Cruze, he still got lost.

One day he wanted to go to Stop and Shop and there is one five minutes away from us. Somehow On Star took him to the one is Hempstead, which is certainly not the safest place for a 90 year old. It was scary for the family.

Finally, dad agreed; we would sell the car. We called GM financial to got the pay off amount. When I told Michelle of it, she said she would buy the Cruze. That was good news, as I wouldn't have to advertise and show the car.

Michelle considered the 2017 Cruze her new car, replacing a 2000 Toyota Camry she got from her grandmother, Liz. This meant, going forward, my wife, Mort or I would take dad to his appointments. If they were on my days off and early appointments, that was fine with me.

All this changed on 10 March. I took dad to the physician for a blood drawer, but he didn't seem right. He had been falling much more, his speech slurred, his hands were swollen. After running a couple of errands and going home for lunch, I took him to the Winthrop University Hospital Emergency Room.

We were in the ER from 11:30 am until I left at 9:30 pm. Dad had a CAT Scan and MRI, which showed he did not have a stoke or concussion. It was finally determined that he had cellulitis with sepsis, which is an infection of the skin and blood.

Dad was in the hospital until he was transferred to a rehabilitation facility in Plainview. Ironically, this place was five minutes from where we used to live and the mother, of a friend, worked there forty-five years ago.

Plainview lock its doors at 7 pm, so I got there around 6:30 pm and wait. Dad didn't show up in the ambulette until 8:30 pm. Plainview put him in a room with three other patients. He finally got settled and I left around 10 pm.

I was able to visit dad the next day, after work; thereafter all nursing home in New York State were locked down, with no visitors allowed. He kept asking me when he was getting out and I didn't have an answer. His health insurance allowed up to twenty days in rehab.

Medicaid bureaucratic red tape galore.

During the time dad was in rehab, I started the process to get him on Medicaid and then into assisted living. I couldn't do this on my own. I hired a company to process the paperwork.

Dad realized that he couldn't stay home alone and acquiesced to the idea of long-term care. I told him, gawd forbid, he if he fell when no one was home, what would happen. Little did I know that those words would haunt me soon after.

I was informed on Friday 20 March that dad would be discharged on Monday 23 March, as his health insurance determined he reached the maximum benefit in rehab. Even after I appealed, a long stay in rehab was denied. I picked him up on Monday 23 March; he was happy to be home.

He wanted a shower, first, and handled it well. Afterward he wanted to relax, have some lunch and take a nap. At dinner he seemed more like his cheerful self.

On Thursday 26 March, I knew something was off. I got him into the shower around 1:30 pm and back in his room a little while later. He then told me he had to go to the bathroom, badly, and said, "I don't feel right."

As soon as I heard those words, I knew something was wrong. I got him back into the bathroom and a few minutes later I heard a thud. I opened the door and he was on the floor, unresponsive.

Marcy called the Wantagh EMS. They arrived in six minutes, flat. Dad had a DNR, but all I had was his health proxy, so they tried to revive him. I knew it wouldn't work, but they continued heroic measures anyway.

The ambulance took dad to Nassau University Medical Center, where they did pronounce him dead. He had a heart attack in the bathroom. Thank goodness he went quick and didn't suffer.

We spoke with the physician, afterwards. He said that when dad arrived, he didn't have a heartbeat. Thus, they didn't try any heroic measures to bring him back.

My first phone call was to Michelle; she cried and screamed. I then called his best friend, John, in Syracuse; I thanked him for everything he had done for dad over the years. I called a couple of his other friends, as well.

On Friday, I had to make the calls to the Social Security Administration, creditors and the Veterans Administration (VA). That was a nightmare; trying to navigate through prompts and having the VA system hang up on me, three times. I finally called out local Veterans Service Agency and spoke to the director. He told me he would have the counselor assigned to dad call me on Monday or Tuesday.

I was numb at this point. I'm not much of a crier, but when dad died, it hit me hard. I was glad that we were able to make him happy and comfortable for nine months. I know he enjoyed living with us.

I asked him once, when you were a kid, what dinosaur did you have as a pet? I was implying he was remarkably old. His reply was, you're looking at your future. I said, I should live that long.

Hopefully in the summer, we can have some sort of service. He wanted to be cremated and I will honour his wish. Since he was a veteran, I'll try to get him into Calverton National Cemetery in eastern Long Island.

While going through his many papers, I found the deed to four plots at a cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, which my grandfather, Martin, bought in 1953. There was note attached to it from Grandma Dorothy that said, "Can't be sold." I called, to check; because Martin in in there, the plot is considered used and cannot be sold.

My father was real paper packrat. He had papers from cars, health insurance, credit cards and medical bills going back over twenty years. I had to separate them all and have roughly eight inches of papers to shred. That will take me days.

I will miss his sense of humour more than anything else. We had a running joke. He knew in four or five years I wanted to move to Florida. He said, "What about me?" I replied, "You either come with us or you'll be dead." Who knew how quickly those words would be true?

At dinner, I'd always come up with something funny that he would laugh at as he ate. He had many friends he cared for and they cared for him.

I'm glad he got to spend time with my kids. While he didn't have much in the way of money to give, he gave his love and affection. What more could we ask?

Raising a glass of orange juice.

It comforts me to know that he his now with his parents, as well as Domino and Daphne. He knew them both and they loved him. When he moved in with us, Dakota took an immediate liking to him. She now goes into his room, wondering where he is.

Dad, I raise a glass of orange juice to you. I love you. I miss you.

Matt Seinberg lives on Long Island, a few minutes east of New York City. He looks at everything around him and notices much. Somewhat less cynical than dyed in the wool New Yorkers, Seinberg believes those who don't see what he does like reading about what he sees and what it means to him. Seinberg columns revel in the silly little things of life and laughter as well as much well-directed anger at inept, foolish public officials. Mostly, Seinberg writes for those who laugh easily at their own foibles as well as those of others.

- Deliveries

- Roadies

- Face Masks in Public

- Super Bowl Slotcar Sunday

- Layers

- The Last DJ

- Rainbow Equality

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Olympic Pullout

- A Piece of Cake

- Disappointments

- Sjef Frenken

- Moribund Ouch

- Kitty Litter

- A Fine How-dy Do

- Jennifer Flaten

- Fashion HQ

- End of World

- Social Butterfly

- M Alan Roberts

- The Dying Insane

- Lessons of the Bucket

- Cries of Rebellion

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- 2014 Year End Review

- Middle Class Screwing

- Random Thoughts

- Bob Stark

- Boomerang

- A Team Canada

- On to Sochi

- Streeter Click

- Grub Street Philosophy: 2

- Boston Blackie

- Police Drama of 1950s

- JR Hafer

- Rosko

- Habit-forming

- Tell Me All About You

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- She Did It

- Beyond the Law?

- Knocked Down

- Jane Doe

- Vintage Radios

- Pink Friday

- Mrs Doubtfire

- M Adam Roberts

- Nick the Busker

- American Idles

- No Greater Love

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- The Future

- Monkey Business