Binding Our Grandchildren

David Simmonds

I’d like to say it was a pleasure to watch the noble lesson in civics that the English language debate, of the last federal election offered. I’d like to say it, but I can’t: the debate was disgraceful.

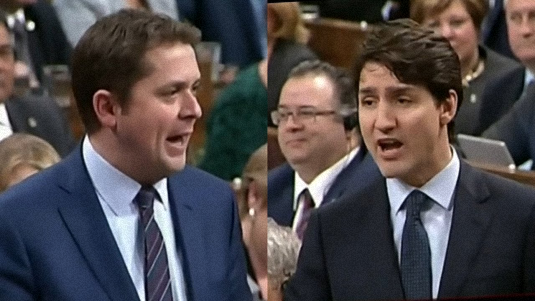

Scheer blows debate, calls Trudeau a criminal.

Andrew Scheer called Justin Trudeau a criminal mastermind at every chance. Justin Trudeau tried to drown out other speakers by talking over them. Maxime Bernier was belligerent. Yves-Francois Blanchet wondered what he was doing in a debate among Canadian leaders.

Elizabeth May and Jagmeet Singh attempted to deliver their massages in a folksy style. They missed their goal by the constraints of time and the format. It wasn’t the greatest learning experience for leader or citizen viewer.

Is there any interest in finding common ground? Is there common ground? Can there be common ground?

I like to think there is some common ground. For example, there are two groups of people, each of which uses the phraseology that we are “handcuffing our grandchildren,” if we simply propel ourselves forward on our current trajectory. Their priorities seem to differ, but I suspect a more fulsome engagement of the two would yield up some areas of agreement.

The first group are the debt reducers. They claim we’re cornered by ever higher public debt, all the while enjoying good times, oblivious to the threat looming over our heads, as if in a brace new world. The debt reducers say our debt level will come back to bite us when interest rates rise or when times turn worse or when no-one wants to invest in the Canadian economy. Debt reducers are not popular at parties.

The other group are the climateers that believer in the science of a climate emergency. They say failure to take more aggressive steps, now, to reduce carbon emissions will make it impossible to meet the targets set out in the Paris Accords. By way of underlining how seriously some take this threat, the Globe and Mail, the other day, carried an article on the rising number of people that are pledging not to have children out of fear the quality of their lives would be so abysmal they are better off not being born.

These seem the extreme end points of political debate.

The peculiar thing is that most people tend towards only one of these two positions. The debt reducers seem to be suspicious of the need to take urgent action on climate change. They argue the environmental lobby has cried wolf before; the gloomy predictions in books such as The Population Bomb and The Limits to Growth have not materialized. Events never turn out as badly as the worst prediction suggests; why should they believe this time?

Climateers believe that adding to the debt is only a consequence of what needs doing to avoid catastrophic climate change. The changeover to a green economy will be more costly the longer we put it off. Those who think otherwise are ostriches hiding their heads in the sand. Besides, if we’re wrong, you still get the bonus of a new green economy ahead of the absolute need for it and this super-productive new economy will take care of the debt load.

It is conceptually possible to be both a debt reducer and a climateer, putting aside the dismissiveness I have attributed to each for the other. I just wish more of them would make their presence felt. Indeed, I would like to put some debt reducers and climateers in a room together in a collaborative, non-partisan setting.

If I could match them up this way, I would even undertake to supply snacks. The discussion, grounded in their common interest in the wellbeing of their grandchildren, would be fascinating. Opportunities emerge when one takes this two-generation approach, admittedly, not even close to the seven-generation approach of the Iroquois, but a big step forward.

For example, investments that may seem imprudent when looked at over the short run of four years may look much different when amortized over the long run of a couple of generations. Priorities would change substantially if weighted against a longer-term vision. What happens quickly falls apart quickly, too; ergo, better a longer-term vision.

Two camps should also be able to find some added common ground on the authority of government. Each wants to wrench the status quo and transform it into something different. Each requires a long lead time, which is why starting now is important. Each is going to want to use the authority of government, whether to try to achieve something bold and new or to conserve something extraordinarily valuable.

Who got my vote?

I voted for the candidate whose party platform has a long-term vision and a short-term plan to realize it. This encourages the collaborative approach and is unafraid to use the authority of government to make it happen, spreading the benefits of all contributions. This shouldn’t be too much to ask.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Two-dollar Store

- More AHA News 2

- Backing Up a Zombie

- The Real Thing

- Counting Steamboats

- Clueless Conduct

- Brands

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Post-surgical Notes

- Julian Assange and Michi

- One Day in America

- Sjef Frenken

- Contact

- Making Ends Meet

- Oversight

- Jennifer Flaten

- School's Out, Forever

- Kid Sickness

- Frugality

- M Alan Roberts

- Freedom

- Death Arrives

- Brain Pump

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Spring Break

- End White Silence

- On-line Reviews

- Bob Stark

- Stanley Cup 2014

- Debriefing

- Olympics 2014 Up-date

- Streeter Click

- Summer & Bradley

- WNBC, c1980

- Leroy Jones Top 40

- JR Hafer

- Why and Wherefore

- The Special Birthday

- Rosko

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- The Joy of Voicemail

- No More Digs

- Not Competent

- Jane Doe

- Speak Now

- A Coffee Mug

- Char-broil 480

- M Adam Roberts

- Lessons in the Park

- Best Mom

- A Father's Heart

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- Harmony

- Monkey Business